Epigraph

“Some recoiled before the prospect of a strange, wider world, and preferred to linger in the shadows of the narrow but familiar place of ancient confinement. Others, the most eager, the most ambitious and most idealistic and optimistic, went towards the light with passionate hopes…. The Jews of the west… stood facing a new and by no means friendly world, marvelous but dangerous, in which any untoward step might be fatal….”

Isaiah Berlin, “Benjamin Disraeli, Karl Marx, and the Search for Identity”

“Dedicated by Yehoshua Moshe. An offering, for the peace of a brother who was slaughtered like a lamb. The day of his birth was a day made hard for him. In his 44th year his blood made a fire offering before God. Mordechai, son of Menachem Baldosa. Wednesday, 9 Nisan [April 6]. Buried 26 Iyar [May 23] of the year [1672]. God welcome him with mercy.”

17th century memorial in the Canton Synagogue, Ghetto degli Ebrei, Venice

Chapter 1

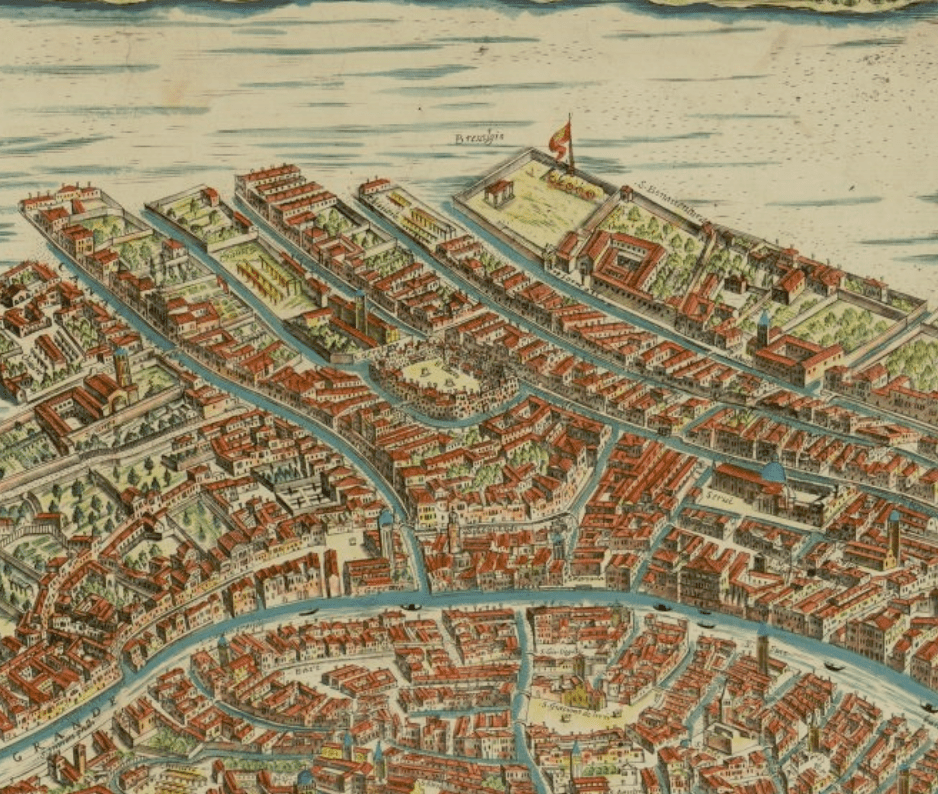

Yehudit Baldosa Parenzo lies alone in her bed in a sleeping alcove in the room she shares with her old aunt, in their family’s apartment in the Ghetto Nuovo, where the Ebrei of Venice dwell in buildings pressed tightly together, bound by encircling walls. The gates are still locked for the night. No Ebreo may pass freely into the rest of the city and no other inhabitants of The Most Serene Republic may enter. The waning moon is low in the sky. A fog has closed in over the canals and calli. In the dark, the far watery horizon encircling Venice has not yet appeared to separate the world above from the world below. It is when pious men in the Shomrim la-Boker societies, the Watchmen for Morning, they who find in the Kabbalah a message inspiring them to gather before dawn, awaken. They wash their hands and prepare to step out of their homes into the chill of this April morning, to meet in the open Campo di Ghetto where they will recite Psalms and penances, waiting for the light.

“Momma.” Yehudit’s younger son, Hayyim, has opened the curtain of her bed alcove and wakes her from a dream in which she was a younger self, not the widow in her middle thirties, waiting in a traghetto about to cross the Grand Canal to take her to the market. For some reason, her brother Mordechai wasn’t coming along.

“It’s the middle of the night,” she mumbles to the boy. “You should be asleep.” She feels the warmth of his head tucked against her neck.

“I’m frightened. There’s shouting outside. There’s a bad smell.”

At that moment the three trumpet blasts of the Ghetto alarm sound. She leaps from bed, crosses the room to rouse old Aunt Nocciolina, grabs a robe, and takes the boy by the arm. The alarm shrieks again and again. In the pitch darkness she hears her older brother Yehoshua shouting, repeating, “Out. Everyone out.” He must have come down from his apartment upstairs. The bells of nearby churches begin clanging. From the calle outside a voice shouts, “Fire!” Only one dark stairwell leads out of her building, all buildings on her street are connected, and the only ways out of the Ghetto are narrow passages leading to locked gates. . . .

Chapter 2

. . . he has always understood that for his own reasons, he would never be, could never be, Grazia’s patron. He wants never to have to reveal or defend his relationship with Grazia to his family or community. He understands that in his position he could not live with his family or in his community and marry—or worse yet, not marry but openly keep company with and support—a woman like Grazia.

In her own world she is ostensibly a Christian, but she has dropped hints about being an orphan distantly related to a family of Ebrei, originally from Spain, that had converted to Catholicism decades ago rather than suffer expulsion or death at the hands of the Inquisition—one of the most prominent Converso or Marrano families ever to have lived in Italy—a family that cruelly denies her claim. This is a fiction, he is sure.

It is no longer unheard of for an Ebreo to marry someone from a Converso family, provided she has openly and sincerely and completely returned to Ebraismo. But to marry a woman who has been a courtesan (and being a so-called honest courtesan is irrelevant in the Ghetto) and expect to maintain his position in the family—that is impossible. Unthinkable. Which brings him back to the inevitability that even if he does the unthinkable and breaks with his family, and brings shame on them, he will be cut off irreparably, irredeemably, from them and such wealth as they have, and she needs a man of wealth. If he remained in Venice there would be no compromise, no third way. If his family cut him off, the Ghetto would cut him off too. To remain in Venice then, to live with Grazia, he would have no choice but to leave Ebraismo, convert. That was repugnant. No one in his family would ever again speak to him or say his name without a curse. Amsterdam is the third way. There will be no forced choice once he is there: she will start a new life; the family will know only what he reports about a Ebrea woman he will tell them he met there, an acceptable subterfuge he has devised. . . .

Chapter 5

. . . Throughout the night, before each slide into the temptations of sleep, her feelings of loss would somehow lead Yehudit from Mordechai’s absence to thoughts of the duties and obligations that would befall her in the daylight, as mistress of the household. This had become her lot in the time after her husband died and she returned from the Parenzo house in Ferrara to her father’s house in Venice. During the long months of Parenzo’s illness she had sat for hours every day at his bedside. Caring for him had been like a captivity for her; she felt as though she never left their room in the Parenzo family’s house, as if the windows were always shuttered, as if every day was a long, silent afternoon in an endless winter. She had banished the new clock, unable to listen to another tick or chime. Sharing a bedroom with the ailing Parenzo had been worse than sleeping alone.

When the thirty days after his death had elapsed, she had no hesitation about kissing her mother-in-law goodbye, leaving the woman standing in the kitchen wringing her hands and moaning about how to get by with only two servants and her own daughters. The moment she closed the Parenzos’ door behind her, Yehudit filled her lungs and stood more upright. When she arrived back in Venice at the Baldosa home, the home she grew up in, when Aunt Nocciolina took her in her arms, Yehudit cried out of relief, more tears than she had shed at Parenzo’s funeral. She had no need then to concern herself about her tomorrows; there was time for tomorrow. . . .

When she had returned from the Parenzo household, it had been easy, a pleasure at first, to be surrounded by her real family, to spend the day with Aunt Nocciolina smiling just to look at her, to visit with her friends from childhood, to tuck the boys into bed in the same room where she had slept, to take part in the household, prepare meals and sit down to eat with them all, to watch Abba or Mordechai read to the boys in the evening, to stroll and talk with Mordechai on Shabbat afternoons.

In time, however, as these simple pleasures became unremarkable, she came to realize there was a less satisfying aspect of her new life. She had started to see that in a way, she was back to being a child to her father and aunt, and even to brother Yehoshua. It was only with Mordechai that she didn’t mind resuming her old relationship, because he respected her, even as he had respected her before her marriage, going back to the times he would come home from his studies in Padua.

Eventually though, she also recognized a hopeful side to returning to her status before her father had arranged the marriage to Parenzo, before the other possibilities of her future had been foreclosed. She recognized that she could, in a way, start her future anew. Praise God, Parenzo had left no unmarried brothers, so even if she had been childless, there was no man with a duty to wed her. She saw that before Parenzo, she had always thought her future would begin by being courted by the young men she wanted to be courted by and marrying one of them. As a widow, she had begun to think that that could be possible again, except she would approach it as a mature woman, a mother, who could make her own choice for her own reasons. . . .